Arc of Attrition – Remember when we were kids in the 70s and our parents would drive us down the M5 to Cornwall with the rest of the UK population, for the summer holidays? After sitting in stationary traffic on the motorway outside Exeter for the first few days, we would finally arrive at the campsite or rented cottage and don our walking boots to stroll along the South West Coast Path. The sun was out, the sky was blue. Perhaps we’d buy an ice cream and play on the beach at St.Ives. Maybe we’d drive up to Land’s End to enjoy the view or stand in awe of the cliffs at Lizard Point. Good times.

Arc of Attrition – Remember when we were kids in the 70s and our parents would drive us down the M5 to Cornwall with the rest of the UK population, for the summer holidays? After sitting in stationary traffic on the motorway outside Exeter for the first few days, we would finally arrive at the campsite or rented cottage and don our walking boots to stroll along the South West Coast Path. The sun was out, the sky was blue. Perhaps we’d buy an ice cream and play on the beach at St.Ives. Maybe we’d drive up to Land’s End to enjoy the view or stand in awe of the cliffs at Lizard Point. Good times.

Little did we know then that one day we would be back. In the dead of winter, in the black of night, we would revisit those nostalgic places of our youth on a 100 mile race that would last up to 36 hours for some, but feel like a lifetime for all of us. The only similarity being that this time, many of us would still be wearing shorts.

What’s A Survival Bag?

The Arc of Attrition, organised by Mudcrew, follows the South West Coast Path from the village of Coverack on the south coast of Cornwall to Porthtowan on its north coast. It is approximately 100 miles, although many suggest it’s further. Elevation ranges from 3000m to 5000m, but is officially 4010m. Suffice to say, this is not a race for the beginner. In fact, you are required to have completed a minimum 100km distance before you can even apply. On top of that, there is a strictly enforced mandatory kit list, which includes a survival bag. Not just a space blanket, but an entire body-cover survival bag.

The Arc of Attrition, organised by Mudcrew, follows the South West Coast Path from the village of Coverack on the south coast of Cornwall to Porthtowan on its north coast. It is approximately 100 miles, although many suggest it’s further. Elevation ranges from 3000m to 5000m, but is officially 4010m. Suffice to say, this is not a race for the beginner. In fact, you are required to have completed a minimum 100km distance before you can even apply. On top of that, there is a strictly enforced mandatory kit list, which includes a survival bag. Not just a space blanket, but an entire body-cover survival bag.

The importance of this came into sharp focus in 2016 when 75% of those that started did not make the finish. Driving rain and storm force winds battered them into submission, and only 28 hardy competitors crossed the finish line of the Arc of Attrition 2016. This year the weather looked almost tropical by comparison. I arrived at registration in Porthtown with the temperature a balmy 4 degrees, although I was not taking anything for granted. The Blue Bar at Porthtowan doubles as both Race HQ and finish line. Runners are then bussed to the start after registration and the race briefing.

Rescue Helicopter

By 9:00am I had successfully passed kit check and been issued with my race number. The next job was to have a GPS tracking device fitted to my backpack. This would be continually monitored throughout the race and if I stopped moving for more than a few minutes, anywhere other than at a checkpoint, the team at Mudcrew would start making enquiries as to my well-being. Furthermore, if I were to press the button on the tracker, an emergency rescue helicopter would be dispatched. “Last year, someone managed to press the button in the car park before the race had even begun” says Race Director Andy Ferguson, by way of warning.

Most normal race briefings go something like this. “Please do not drop litter or you will be disqualified. Shut gates behind you, and there are a few pregnant cows around so do steer clear of them if you can. Have a great race everyone”. The race briefing for the Arc of Attrition 2017 included such gems as “Don’t wander off the path because there are numerous abandoned tin mines out there and the trackers don’t work at the bottom of a mine shaft” and “You’ll be running on some exposed cliff edges so make sure your head torch is working and turned on during the 13 hours of darkness”.

Most normal race briefings go something like this. “Please do not drop litter or you will be disqualified. Shut gates behind you, and there are a few pregnant cows around so do steer clear of them if you can. Have a great race everyone”. The race briefing for the Arc of Attrition 2017 included such gems as “Don’t wander off the path because there are numerous abandoned tin mines out there and the trackers don’t work at the bottom of a mine shaft” and “You’ll be running on some exposed cliff edges so make sure your head torch is working and turned on during the 13 hours of darkness”.

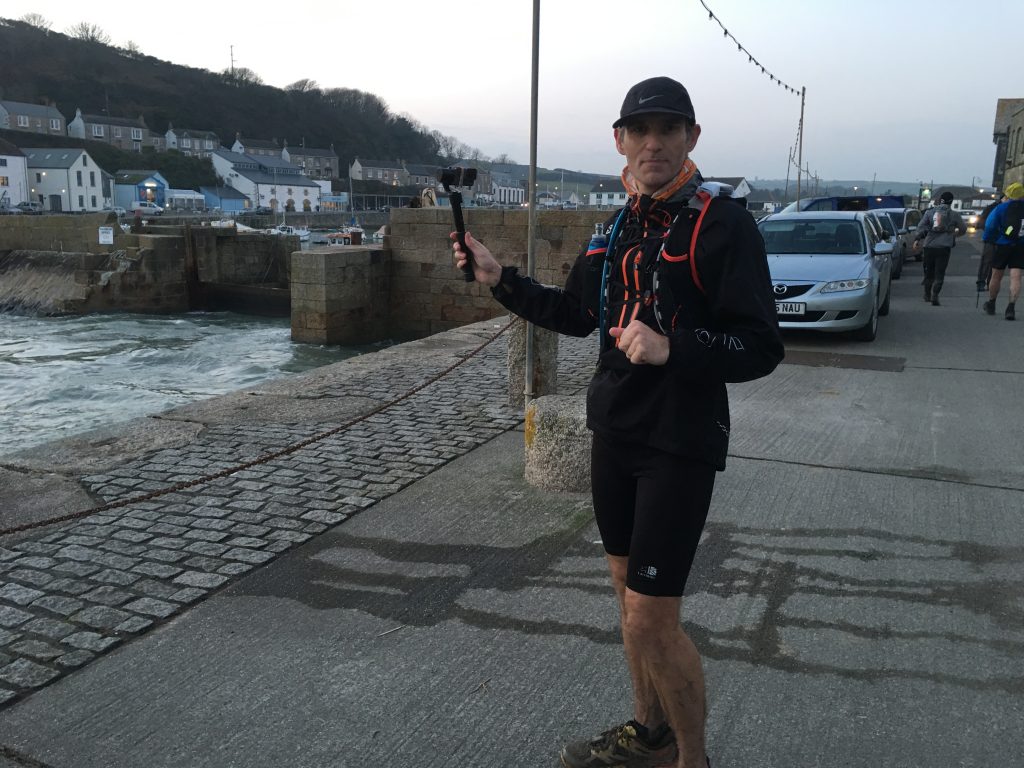

With that, 109 of us boarded the busses. We had an hour’s journey to Coverack. An hour in which to contemplate what lay ahead. I had goals, but no expectation that I would achieve them. I had fears but every expectation that I should overcome them. As well as running the race, I would be carrying a camera and trying to document my Arc of Attrition experience. This comes with its own set of problems over and above the actual running. Achieving good quality sound in howling wind meant carrying a separate audio recorder and mic. In order to get stable footage I needed a gimbal, which is basically a heavy, battery-powered selfie stick. I needed extra camera batteries, spare SD cards and a spare camera in case one packed up. Along with two head torches, survival bag, other clothing and water bottles, this made for a rather weighty Salomon vest!

Arc of Attrition

Suitably wrapped up against the ever increasing wind, we set off just after midday. After a few hundred metres on the road and a short climb, we were on the coastal path. The terrain was almost immediately uneven, the mud claggy and the elevation intense. In the first 10 miles to Lizard Point, my Garmin clocked me at over 600m total gain. One minute we would be high up on the cliffs with stunning views along the coast. The next we were on a rocky beach timing our run across the cove to avoid the oncoming waves. It was windy and cloudy, but bright with no rain. I had settled into the middle of the pack and pressed on. The running between miles 10 and 24 was much easier than the first 10 and I was ahead of my very loose schedule when I arrived at the first checkpoint at Porthleven. The Arc of Attrition course was split by four official checkpoints, all of which were located indoors in pubs or hotels and all served hot food. However, there were numerous points on the course where a runner’s own crew could provide additional support.

Suitably wrapped up against the ever increasing wind, we set off just after midday. After a few hundred metres on the road and a short climb, we were on the coastal path. The terrain was almost immediately uneven, the mud claggy and the elevation intense. In the first 10 miles to Lizard Point, my Garmin clocked me at over 600m total gain. One minute we would be high up on the cliffs with stunning views along the coast. The next we were on a rocky beach timing our run across the cove to avoid the oncoming waves. It was windy and cloudy, but bright with no rain. I had settled into the middle of the pack and pressed on. The running between miles 10 and 24 was much easier than the first 10 and I was ahead of my very loose schedule when I arrived at the first checkpoint at Porthleven. The Arc of Attrition course was split by four official checkpoints, all of which were located indoors in pubs or hotels and all served hot food. However, there were numerous points on the course where a runner’s own crew could provide additional support.

Despite having to look after our two small children, my wife, Victoria had agreed to crew for me. I’m afraid I am guilty of requesting a monumental effort on her part, to meet me at some 15 locations along the route. I’ve come to realise, over my ultra-running career, that in terms of nutrition, little and often is good for me. I have tried all sorts of food and drink combinations to prevent gastric problems. I’m not going to sit here and tell you what to eat or drink, but what is currently working for me is a meal replacement drink called Huel. Unfortunately, it’s not something you can stick in a bladder or soft flask, as it is rather grainy. The plan was that I would have water and Red Bull in my two front flasks and Victoria would provide my Huel drink every 7-10 miles.

Despite having to look after our two small children, my wife, Victoria had agreed to crew for me. I’m afraid I am guilty of requesting a monumental effort on her part, to meet me at some 15 locations along the route. I’ve come to realise, over my ultra-running career, that in terms of nutrition, little and often is good for me. I have tried all sorts of food and drink combinations to prevent gastric problems. I’m not going to sit here and tell you what to eat or drink, but what is currently working for me is a meal replacement drink called Huel. Unfortunately, it’s not something you can stick in a bladder or soft flask, as it is rather grainy. The plan was that I would have water and Red Bull in my two front flasks and Victoria would provide my Huel drink every 7-10 miles.

13 Hours of Darkness

Soon after leaving Porthleven, the light was gone. Head torches donned, we made our way 14 miles round the coast to Penzance and the second official checkpoint at 38 miles. Penzance is a fair-sized town and running in, and then out the other side, made for a good few miles of flat, urban running on roads and paths. In the grand scheme of things, it didn’t last long and we were soon climbing hills, traversing streams, crossing little wooden bridges and climbing over boulders again. In the daylight, the path up the steep steps to Minack open air theatre is beautiful. In the dark, when you can’t really tell how steep the drop is, it’s scary. But once at the top, I met my wife with two sleeping children in the back of the car and I was filled with renewed vigour, having made it to 50 miles.

The Arc of Attrition is a self-navigation race. This means that for most of the course, the event organisers have not placed any direction signs along the route. The good news is that the South West Coast Path is relatively well marked as it is. All you have to do is keep following the little acorn sign. Simple, yes? Well, not if you are me apparently. What’s annoying is that I even had the route map on my watch to refer to. I just didn’t refer to it often enough, and as the night drew on I regularly found myself 500 metres off course on another path and would have to track all the way back. On one occasion I led two other runners up a huge incline only to find we had to come all the way back down again. A little later, I followed a chap who looked like he knew where he was going, only for him to lead us both into bramble bushes up to our chests.

The Arc of Attrition is a self-navigation race. This means that for most of the course, the event organisers have not placed any direction signs along the route. The good news is that the South West Coast Path is relatively well marked as it is. All you have to do is keep following the little acorn sign. Simple, yes? Well, not if you are me apparently. What’s annoying is that I even had the route map on my watch to refer to. I just didn’t refer to it often enough, and as the night drew on I regularly found myself 500 metres off course on another path and would have to track all the way back. On one occasion I led two other runners up a huge incline only to find we had to come all the way back down again. A little later, I followed a chap who looked like he knew where he was going, only for him to lead us both into bramble bushes up to our chests.

Remote Coastline

I made it to Land’s End and the third checkpoint still feeling strong, but now behind where I had wanted to be in terms of time. The temperature had started to drop significantly and we were approaching the most technically demanding section of the course. I downed a bowl of chicken soup and considered changing my socks. It felt like too much effort, so on I went. Having run with people on and off for much of the race thus far, by now it was thinning out considerably. I was to learn later that by Land’s End or before, 23 runners had dropped out. I set off down a path out of Land’s End at around 2am. I got about 400m down the path and panicked that I had gone wrong again. I walked back up, only to find I had been right all along.

Parts of this next section between Land’s End and Pendeen Watch were very boggy. However, 60 miles into a 100 mile race you start to care very little whether your feet are wet or not. In fact, sometimes it can be a real relief to put your feet in icy-cold water. If you’re wearing good shoes and socks, they should drain quickly so you won’t carry the extra weight of waterlogged footwear for long. By now, my Garmin was reporting 3000m elevation and it was only about to get worse. It was still dark at 65 miles when I saw Victoria at Pendeen Watch Lighthouse, before I headed out for a 14 mile section to St.Ives that is the most difficult and technically challenging on the Arc of Attrition course. It’s also the most remote, so any problems here and you’re on your own for longer than you might be otherwise.

Parts of this next section between Land’s End and Pendeen Watch were very boggy. However, 60 miles into a 100 mile race you start to care very little whether your feet are wet or not. In fact, sometimes it can be a real relief to put your feet in icy-cold water. If you’re wearing good shoes and socks, they should drain quickly so you won’t carry the extra weight of waterlogged footwear for long. By now, my Garmin was reporting 3000m elevation and it was only about to get worse. It was still dark at 65 miles when I saw Victoria at Pendeen Watch Lighthouse, before I headed out for a 14 mile section to St.Ives that is the most difficult and technically challenging on the Arc of Attrition course. It’s also the most remote, so any problems here and you’re on your own for longer than you might be otherwise.

Suffering Hallucinations

Thankfully, it was during this section that dawn finally emerged. Although this made navigation easier, I was now seriously slowing down. Victoria had been there for me every 7 miles or so to give me a pep talk and send me on my way. Now I was alone, hardly able to run at all on the terrain and willing St.Ives to appear round the corner with every step I took. In other news, I was now also suffering hallucinations. “There are sheep over there”. No, just some small white rocks. “There’s an old woman bending over a wall”. No it’s foliage. “Look, a tank!” No, a tree. I eventually got used to this and found my sub-conscious’ creative imagination rather entertaining.

It took forever, but at last, in the middle of a hail storm, I arrived at the final checkpoint in St.Ives. The worst was over, but those 14 miles had taken me over 5 hours. My loose schedule had been to try and finish in 26 hours. That was now long gone. The next target was to get in under 30 hours. If you can finish the Arc of Attrition in that time, you achieve their coveted gold buckle. After 30 hours it’s a red buckle. I had six hours on leaving St.Ives to cover 22 miles. In any normal race, under normal circumstances, 22 miles in 6 hours is almost a given. But when you’ve run 78 miles immediately before, through the night, in freezing temperatures, across some of the most challenging terrain you will find anywhere in the country, it’s by no means a certainty.

It took forever, but at last, in the middle of a hail storm, I arrived at the final checkpoint in St.Ives. The worst was over, but those 14 miles had taken me over 5 hours. My loose schedule had been to try and finish in 26 hours. That was now long gone. The next target was to get in under 30 hours. If you can finish the Arc of Attrition in that time, you achieve their coveted gold buckle. After 30 hours it’s a red buckle. I had six hours on leaving St.Ives to cover 22 miles. In any normal race, under normal circumstances, 22 miles in 6 hours is almost a given. But when you’ve run 78 miles immediately before, through the night, in freezing temperatures, across some of the most challenging terrain you will find anywhere in the country, it’s by no means a certainty.

Adrenaline Surge

Thankfully the first 6 miles between St.Ives and Hayle was flat and fast. I made every effort to cover this as quickly as possible and managed to pass a few tired legs as I went. The sand dunes from Hayle to Godrevy are the only section of the entire course that Mudcrew mark out to help you navigate. Running through sand doesn’t sound good news at all, but it was surprisingly easy given what had gone before. With 11 miles to go, I was back on the hills. This time though, the trails were much more like those you would find on any ‘normal’ trail race. I was running and walking, running and walking the best I could, but I could feel my legs were done. When I arrived at a huge valley with 6 miles to go, my heart sank. I thought, there’s no way I can do it now. Hobbling down the steps and crawling up the other side was about the best I could muster.

Thankfully the first 6 miles between St.Ives and Hayle was flat and fast. I made every effort to cover this as quickly as possible and managed to pass a few tired legs as I went. The sand dunes from Hayle to Godrevy are the only section of the entire course that Mudcrew mark out to help you navigate. Running through sand doesn’t sound good news at all, but it was surprisingly easy given what had gone before. With 11 miles to go, I was back on the hills. This time though, the trails were much more like those you would find on any ‘normal’ trail race. I was running and walking, running and walking the best I could, but I could feel my legs were done. When I arrived at a huge valley with 6 miles to go, my heart sank. I thought, there’s no way I can do it now. Hobbling down the steps and crawling up the other side was about the best I could muster.

It’s amazing, though, what a dose of adrenaline can do. I arrived at my final stop in Portreath, a broken man, believing I had 5 miles to go. Victoria thrust a coffee in my hand and one of the Mudcrew staff (confusingly called Andy, like about 5 other members of the Arc of Attrition team!) told me I had 3.5 miles to go. “What?! I thought it was 5! I’m trying to get in under 30 hours”. “Well you can still make it”, he said. That was it. It was all the motivation I needed to fair sprint for the line. There was, however, one final hiccup. Andy had meticulously told me exactly where to go to get out of Portreath and back onto the coast path. But in my delirium, I hadn’t heard a word he had said and I ended up knocking on the door of some random house at the top of the village to ask where I was supposed to go. Eventually back on the coast path, I ran as fast as my legs would carry me.

I Want That Gold Buckle!

Those last three miles turned out to be four miles and were not without two final stings. Two more valleys to traverse before the final drop into Porthtowan. At the top of the hill I shouted to a bystander to ask the time. I had ten minutes to get down the hill, round the village and back to the Blue Bar.

Those last three miles turned out to be four miles and were not without two final stings. Two more valleys to traverse before the final drop into Porthtowan. At the top of the hill I shouted to a bystander to ask the time. I had ten minutes to get down the hill, round the village and back to the Blue Bar.

Thankfully, it really wasn’t far and I crossed the line just before darkness fell after 29 hours and 50 minutes of a 100 mile race the like of which I have never experienced before. I was the last person across the line to get an Arc of Attrition gold buckle. I thought my finish was tight, but the last runner out on the course cut things even finer. She crossed the line 12 seconds before race cut off, in 35 hours, 59 minutes and 48 seconds. Incredible.

I am tremendously proud of my gold buckle and in awe of everyone who even started the A rc of Attrition 2017. What a race. It is growing each year and is set to be a classic. A real challenge, on a tough course in a stunning part of the world. What’s not to love?

rc of Attrition 2017. What a race. It is growing each year and is set to be a classic. A real challenge, on a tough course in a stunning part of the world. What’s not to love?

As for the organisation, I cannot speak highly enough of Mudcrew and their staff. Although there were only four official checkpoints, Mudcrew had staff out on the course at almost every accessible location, offering directions, nutrition, hydration, medical and moral support. Priceless. I will almost certainly be back next year to try and knock a couple of hours off my time.

If you have found this Arc of Attrition race report helpful and interesting, please do share it with your friends and anyone you know who might be considering taking part in this awesome Mudcrew event in the future. Thanks to Andrew Benham for the photos.

Pingback: Brighton Half Marathon | Too Short for 3 Years | Film My Run

Pingback: South Downs Way 100 | A Nightmare from Start to Finish | Film My Run

Pingback: Beacons Ultra, Wales | Force 12 Events | Film My Run